Nowhere in the Global South has photography been received so enthusiastically as on the coast of West and Central Africa. Only twenty years after the new medium was introduced in Paris in 1839, it suddenly spread worldwide. Thus, a flourishing photographic culture also developed between Dakar and Luanda, writes the Museum Rietberg about its exhibition “The Future is Blinking”, which will open on 18 March 2022.

For the first time in Switzerland: photographs by professional photographers from West and Central Africa

The exhibition “The Future is Blinking” shows for the first time in Switzerland photographs by professional photographers from West and Central Africa taken from the late 19th to the early 20th century. The photographs are mainly from the collection of the renowned ethnologist and photo historian Christraud M. Geary of the Museum Rietberg. They are occasionally supplemented by loans from international and national collections as well as a sculpture by the contemporary artist Yinka Shonibare.

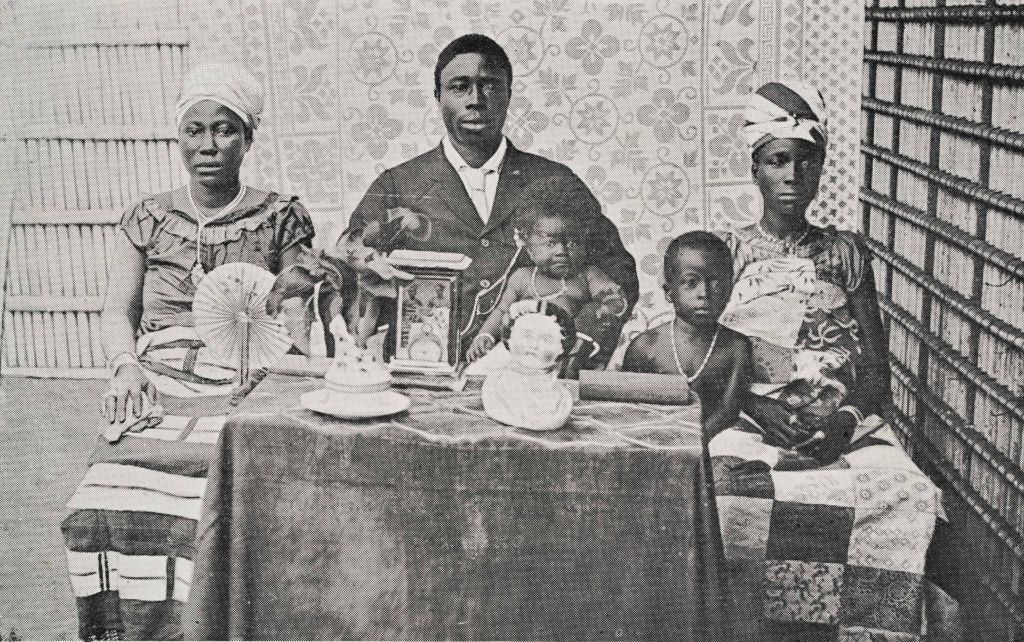

“Merchant family with valuable possessions, including a framed photograph”. Unknown, Jacqueville, Ivory Coast, c. 1902, autotype, Museum Rietberg Zurich, Christraud M. Geary Collection, purchased with funds from the Rietberg Circle.

Based on one hundred original prints, the exhibition does not think of the photographic history of West and Central Africa from the perspective of the Global North, but focuses on its peculiarities, artistic practice and conventions of representation. The portraits shown nevertheless seem strangely familiar. As with photographs circulated on social media today, the photographs represented individual wishful images and created new realities. The exhibition at the Museum Rietberg also draws surprising references to traditional carving art from the region, to itinerant photography in Switzerland and to the latest fashion photography from the USA.

Result of a self-determined photographic culture

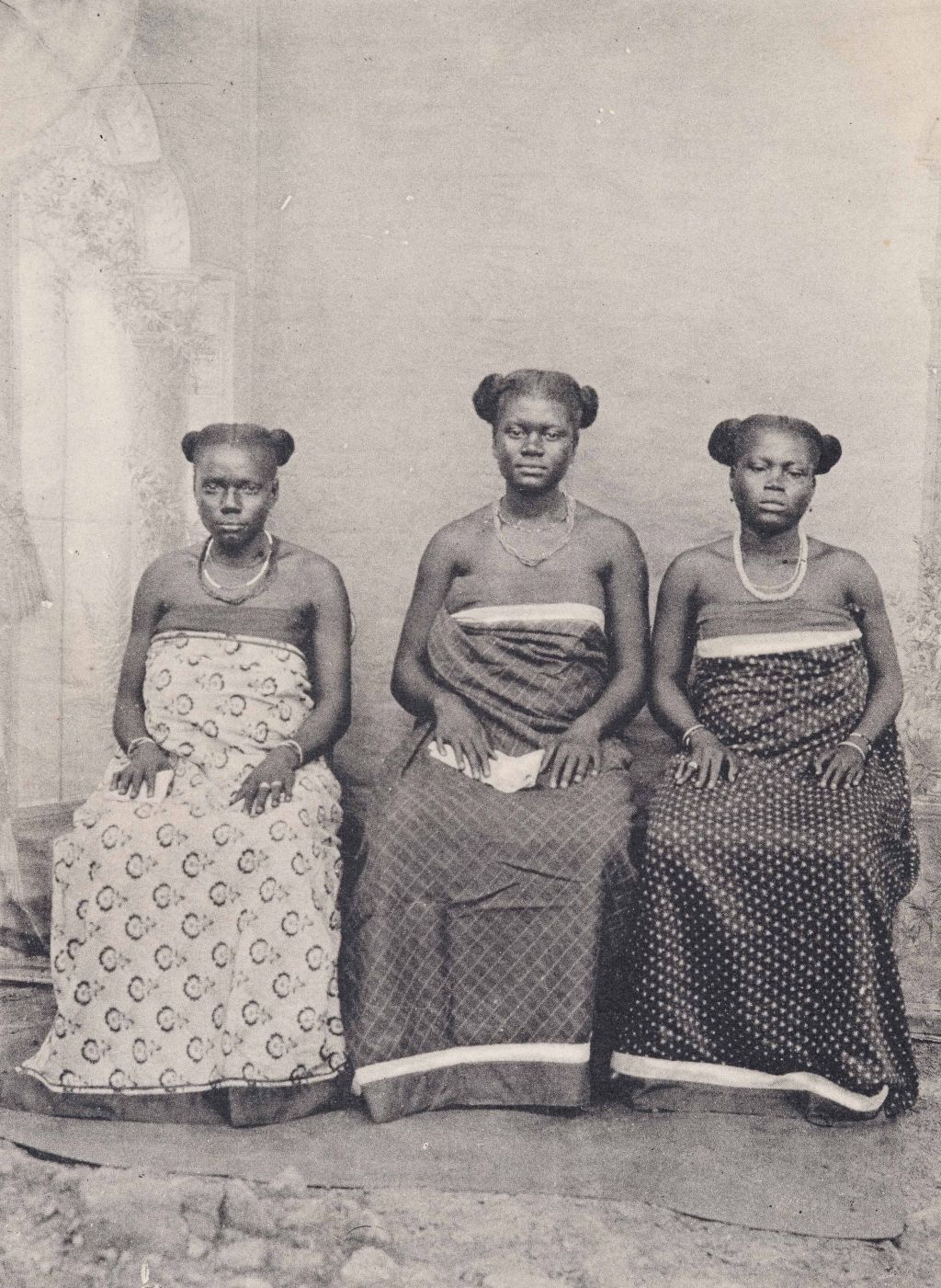

The earliest photographs from the coast of West and Central Africa are the result of a self-determined photographic culture and thus differ greatly from colonial photography with its depictions of African people that were marked by prejudice. At a time when life was dominated by colonial oppression, the outdoor studio became a place of self-determination, self-expression and identity formation. In the process, people used the potential of photography to create new realities. Women in particular were open to the new medium. They used their beauty together with gorgeous textiles as a resource in front of the camera to articulate their position in society. The strong presence of women in studio photography of West and Central Africa contrasts with their absence in archives and the muteness of African women in Western historiography.

The earliest photographs from the coast of West and Central Africa are the result of a self-determined photographic culture and thus differ greatly from colonial photography with its depictions of African people that were marked by prejudice. At a time when life was dominated by colonial oppression, the outdoor studio became a place of self-determination, self-expression and identity formation. In the process, people used the potential of photography to create new realities. Women in particular were open to the new medium. They used their beauty together with gorgeous textiles as a resource in front of the camera to articulate their position in society. The strong presence of women in studio photography of West and Central Africa contrasts with their absence in archives and the muteness of African women in Western historiography.

Most early pictures on postcards or in albums

Most of the early images of West African photographers are now printed on postcards or stuck in albums in archives in the Global North. For a long time, it was assumed that the names printed on the back of such photographs were Eur0pean photographers. Only in the last twenty years has research revealed that most studio photographs have a local authorship. The pioneers were young men from the urban elite with similar biographies. Many of them came from Sierra Leone or Gambia and were educated in missionary schools. They led restless lives, travelling by steamboat along the coast from Dakar to Luanda with their mobile open-air studios; they saw themselves as artists and mastered the latest techniques of their time.

“Three Women”. Khalilou (Senegalese, active around 1900), Libreville, Gabon, 1910, collotype, Museum Rietberg Zurich, Christraud M. Geary Collection, purchased with funds from the Rietberg Circle.

Together with their clientele, photographers from the region created unique portrait photographs in open-air studios. The exhibition deciphers the codes visible in the photographs and makes the images speak. “The Future is Blinking” focuses on self-dramatisation in front of the camera long before the topic became highly topical through digital social platforms. Although the identities of most of those depicted have been lost in this way over time, we encounter their gaze and realise that they had the final say in shaping the photographs.

Photographers also provided the equipment for the portraits.

The photographers provided their clients with a stage and equipment for these transformations. In addition to backgrounds, this also included decorations and accessories. Depending on their intention, the subjects chose the appropriate elements and mixed them with things from their personal possessions. Photo backdrops as projection screens intended to beautify and improve the world were an important element of the photographs. To express their modernity, those depicted also resorted to imported accessories such as pith helmets, umbrellas or plastic flowers. Depending on the occasion for the studio visit, traditional accessories charged with local significance such as jewellery, fabrics or insignia of political power were also used.

“Portrait of a woman with fashionable hairstyle and umbrella”. Unknown, Nigeria (?), c. 1890, albumen print, Museum Rietberg Zurich, Christraud M. Geary Collection, purchase with funds from the Rietberg Circle.

Textiles played a special role in portrait photography. They provided movement by breaking up the balanced picture compositions with their asymmetrical patterns. With their choice of fabrics, the sitters signalled their social status, their affiliation to a certain regional group or their relationship to each other. Fabrics could also recall puberty rites or funerals, thus embodying memory in the souvenir photograph.

Photography did not fill a void in West and Central Africa. Rather, it has linked up with other local arts, has stood in a reciprocal relationship or even entered into symbioses. These relationships with other arts have created the special aesthetics of West and Central African photographic culture. Unlike in the Global North, it was not painting that shaped it, but sculpture and the performative arts. The relationship between photography and sculpture is being addressed for the first time in an exhibition. Instead of chisels, photographers used graphite pencils to edit their artworks so that they came as close as possible to the ideal human being. With these interventions, the traces of life were erased so that the faces appeared like a mask – an ideal adopted from carving art.

“The future is blinking” is a quote by the Ghanaian photographer Philip Kwame Apagya (*1958) from the film Future Remembrance (1997). Apagya is referring to what he sees as the most important task of photography in Ghana, namely to create memories for future generations with idealised portraits. Studio photography of the late 19th century also had the future in mind by staging wishful images for posterity.

Portraits also sold as postcards to travellers

Many of the photographs in this exhibition were sold as postcards to travellers shortly after their production. With the transition of private photographs into the public sphere, the images became separated from the narratives and practices that charged the photographs with meaning and by which the sitters remained recognisable.

The exhibition raises questions about our image of Africa, about foreign and self-perception, about exoticisation and ultimately about the representation of the Other. The growing popularity of the picture postcard in the early 20th century offered photographers a lucrative field of business. African postcard clients were familiar with Europe’s image hunger for the exotic and used this to their advantage by staging images that appealed to visitors from abroad. They also used portraits commissioned privately by families. Provided with generalising captions, the depicted persons lost their identity; depicted women went from being body-subjects to body-objects.