The driver of rising real estate prices.

10.10.2023On behalf of the Federal Office of Housing (BWO), the Amt für Raumentwicklung Kanton Zürich and the cantonal planners of the Zurich metropolitan area (AG, LU, SG, SH, SZ, TG, ZG), IAZI AG and the Center for Regional Economic Development (CRED) of the University of Bern conducted a study in an attempt to quantify the drivers of rising property prices. The study sought to identify the most relevant factors that have contributed to the described rise in housing costs in Switzerland. A special focus was placed on the role of spatial planning.

An abridged version of the study in German language can be downloaded as a PDF here; the full study in German language is available as a PDF here.

The study investigated possible causes of rising housing costs in Switzerland. The housing market was divided into two segments, the owner-occupied and the rental market, and therefore both the prices for residential property (single-family houses and condominiums) and net rents offered were taken into account.

The starting point is the sharp rise in property prices since 2000.

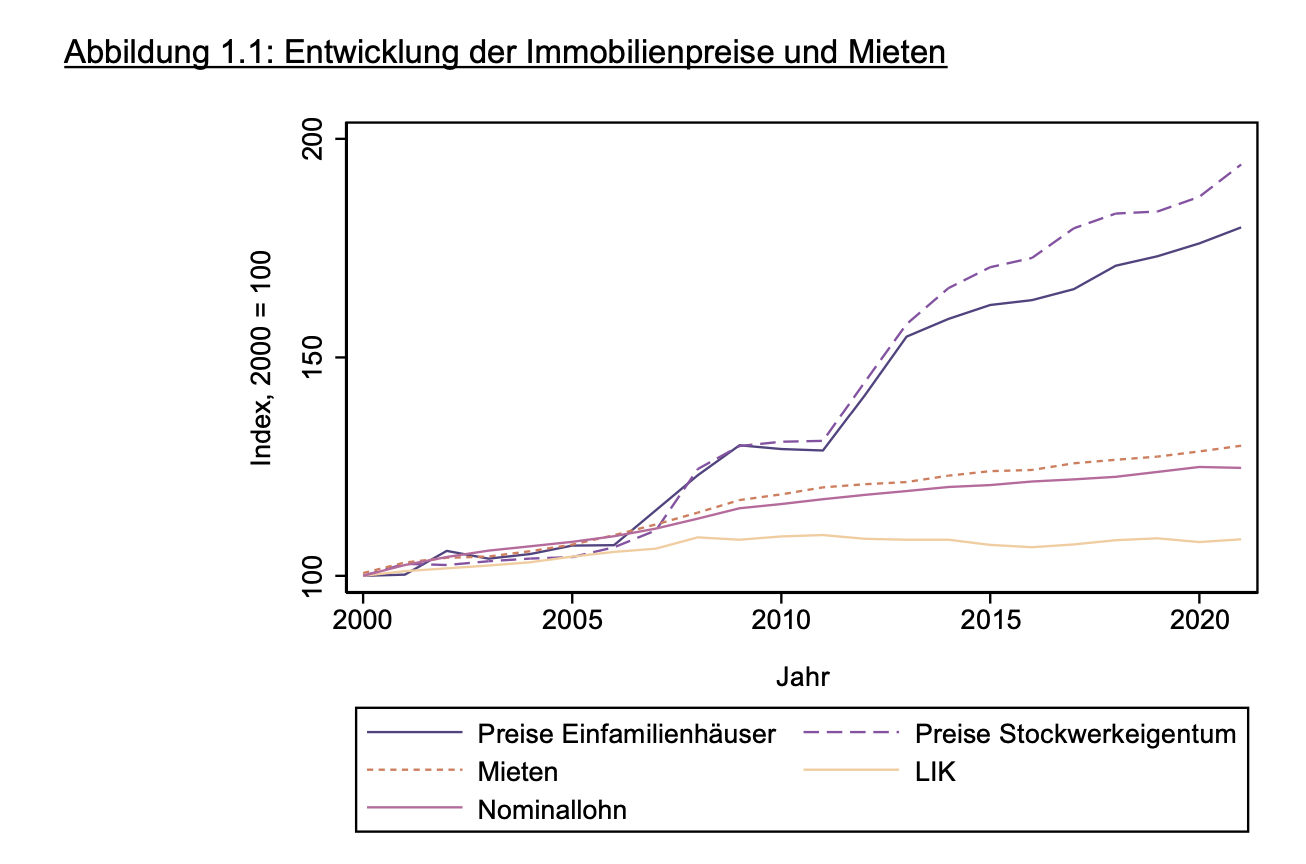

The study is based on the following price trends in the two segments, as the study’s summary states: “Between 2000 and 2021, prices for single-family homes in Switzerland rose by around 80%, and those for condominiums by as much as 94%. At 30%, rents have also risen more strongly than the general cost of living (+8%) or nominal wages (+24%) during this period.”

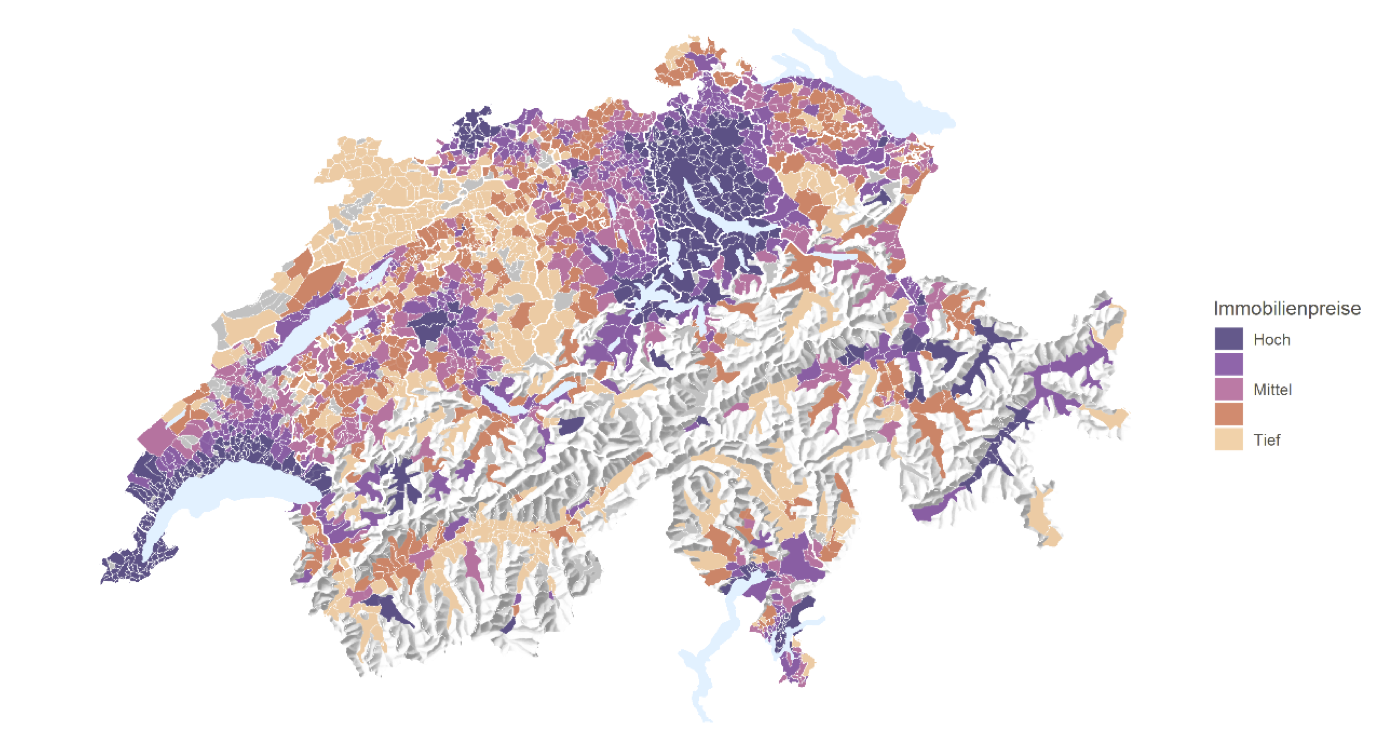

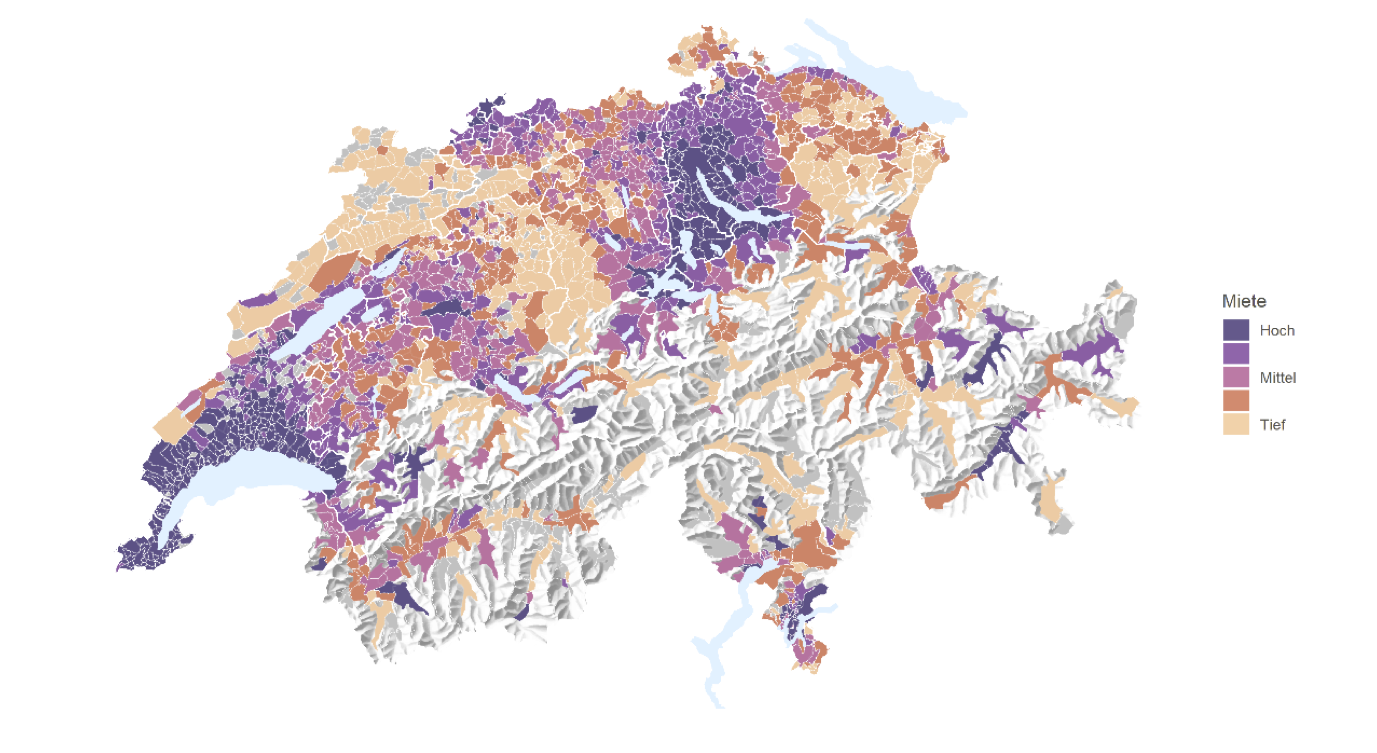

In addition to this temporal variation, there is a high spatial variation in housing costs, which is at least as relevant. The average property price in a municipality that is among the most expensive 20 per cent of municipalities (80 per cent quantile) is 70 per cent higher than the average price in the cheapest 20 per cent of municipalities (20 per cent quantile). This example illustrates that housing costs vary significantly not only over time but also across space.

And these are the results

In its media release, IAZI AG summarises the results of the study as follows: “Higher housing costs result from higher demand in cities and urban agglomerations, population growth, rising incomes (greater affluence), the shortage of supply (scarce building land, few zoning measures, zoning planning) and more expensive, higher-quality construction. These cost drivers influence the development of residential property prices by 66% and that of rents by 71%.

The influence of spatial planning measures and instruments on housing costs is also measurable. The magnitude is between 6-8%.

The mandate of spatial planning to shape the landscape for long periods of time thus has a value and a price. The value lies in the preservation of the environment with the intention of preventing negative influences (soil sealing, urban sprawl, etc.). In addition, an appropriate design space should be secured for future generations. The study states that the “slightly higher housing costs in the present” must be accepted. “They are the price to pay for preserving the environment for future generations”.

Higher construction costs (material, standard, etc.) as well as other factors (region, luxury, financing, servitudes, hoarding of building land, housing consumption/person, etc.) also influence the development of housing costs (15%-25%).

Conclusion

The study concludes that spatial planning has instruments at its disposal “that can have a dampening effect on housing costs in Switzerland. However, the scope for action and effectiveness of spatial planning are strongly influenced by the legal, political and economic context. Spatial planning also operates in an area of tension between different demands. In particular, it is necessary to weigh up the negative externalities of uncontrolled settlement growth on the one hand and social costs such as higher housing costs on the other. This report has only looked at one side of this trade-off – housing costs. With an appropriate data basis, the other side of this trade-off could also be examined in the context of further analyses. In addition, the findings should be translated into concrete approaches for action.